|

|

|

|

|

|

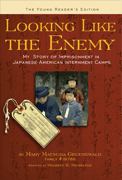

Young Reader's Edition |

|

ISBN 978-0-939165-58-2 |

![]()

Originally published February 14, 2012 at 8:38 PM | modified February 15, 2012 at 10:24 AM

Carrying the pain for 70 years: Japanese Americans' internment

Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, along with her parents and brother, was among some 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans on the West Coast sent to relocation camps in World War II. Their age, occupation — even citizenship — were irrelevant under Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942.

By Jack Broom

Seattle Times staff reporter

ERIKA SCHULTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, 87, holds an old pickle jar in which she collected more than 100,000 tiny shells during her internment at Tule Lake.

ERIKA SCHULTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, 87, holds an old pickle jar in which she collected more than 100,000 tiny shells during her internment at Tule Lake.

She remembers the guns — military rifles with bayonets — held by a line of grim-faced soldiers watching her every move.

What could she, a girl of 17, have done to deserve this?

Why were her parents being treated as dangerous criminals? They ran a 10-acre strawberry farm on Vashon Island and hadn't caused any trouble.

"I felt like they were going to take us away to shoot us," said Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, 87, now living in Seattle's Wedgwood neighborhood. "I had this terrible feeling of doom and gloom and depression."

The answer to the question "why," racing through her mind that day in May 1942, is as simple as it is unsettling: More than six decades later, it would become the title to Gruenewald's memoir and describes her family's sole offense: "Looking Like the Enemy."

Gruenewald, along with her parents and 19-year-old brother, was among some 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans on the West Coast sent to relocation camps in World War II.

Their age, occupation — even citizenship — were irrelevant under Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942.

Coming a little more than two months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, the order gave the secretary of war power to define "military areas" and decide who could or could not remain there.

As Sunday's 70th anniversary of Roosevelt's order approaches, lectures, art exhibits, film screenings and other events are planned by community groups marking the "Day of Remembrance."

Bif Brigman of the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington in Seattle said the lesson from Executive Order 9066 is that "America must continue to be vigilant and protect innocent men, women and children from racial discrimination, wartime hysteria and prejudice — even when it is perpetrated by the highest reaches of our government."

Gruenewald will speak at 11 a.m. Wednesday at South Seattle Community College and at 1 p.m. Feb. 28 at North Seattle Community College, telling a story she kept inside for decades, its details still painful.

She remembers her family's fear of reprisals after the Pearl Harbor attack, a fear that increased as FBI agents searched homes and possessions of Japanese residents on the West Coast.

In an attempt to avoid trouble, her Japanese-immigrant parents, Heisuke and Mitsuno Matsuda, burned all their Japanese mementos. Piece by piece, they fed precious family photographs, phonograph records, books — even ceremonial dolls — into the oil stove that heated their home.

"We didn't want to look even faintly sympathetic to Japan, the country responsible for the Pearl Harbor devastation," Gruenewald said.

Nevertheless, posters with "Instructions to all Japanese" appeared on telephone poles on Vashon Island in May 1942, informing them that they were to report in eight days, bringing only the belongings they could carry.

The order applied even to those who, like Mary and her brother, Yoneichi, were born in the United States and therefore American citizens.

After a ferry ride to Seattle, Gruenewald's family joined others aboard train cars with blackened windows for a three-day ride to an "assembly center" outside Fresno, Calif., and later transferred to the Tule Lake Relocation Center, a camp on a dry lake bed in California's northeast corner.

Gruenewald doesn't know if she could have coped with the fear, anger and depression of being at the camp without her mother's steady wisdom.

"Mama-San," as Gruenewald called her, embodied two important elements of Japanese culture: "Shikata ga nai," translated as, "It cannot be helped," and "gaman," meaning patience, perseverance and self-restraint.

"Twenty years from now," her mother said, "we may have nothing more than the memories of how we conducted ourselves with dignity and courage during this difficult time. What kind of memories do we want to have then of how we faced these difficulties now?"

Mama-San even came up with a hobby to keep Mary from brooding, encouraging her to collect the small, white shells of creatures that had lived in the long-ago lake the camp was built on. "There were gazillions of them all over. Just scrape off the top layer of soil and there they are."

Gruenewald made jewelry and wall hangings from the shells, sending them to friends on Vashon.

In 1943, camp residents were asked if they would pledge their loyalty to the United States and serve in its military — difficult and divisive questions that forced internees to reconcile what they wanted to believe about America with the conditions of their confinement.

Gruenewald and her family agreed to the pledge, and their decision paved the way for her and her brother to leave the camps in 1944. For Yoneichi, that meant joining the Army, serving in Italy in the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Gruenewald, who had worked as a nurse's aide at camp, joined the Cadet Nurse Corps and was assigned to a small hospital in Iowa, where she began the work that would become her career.

Her parents remained in camps until September 1945, spending their final year at Minidoka, in Idaho.

More than four decades later, the 1988 Civil Liberties Act acknowledged the injustice and authorized a payment of $20,000 to each living survivor of the camps.

By then, Gruenewald's mother, father and brother had died, and she wished they would have been alive, not for the money, but to hear the government admit that what happened to them was wrong.

Gruenewald, then working for Group Health Cooperative, gave her reparations check to the Group Health Foundation to help provide medical services to those in need. She retired from Group Health in 1990 and is known for founding its consulting-nurse service that became a national model.

In 1999, Gruenewald decided to put her story in writing, primarily so her three grown children would know the details. At the urging of a writing teacher, the story expanded into a book, published in 2005.

Intending no disrespect to her culture's tradition of reticence, Gruenewald said there's a time to be silent, but also a time to speak up. "We are all responsible to each other, to protect each other's rights and privileges in a democracy."

The anti-Muslim backlash that spread across the country in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks is a reminder that — in a time of crisis — fear and prejudice can threaten important principles, she said.

Among her reminders of the camps is a gallon pickle jar full of tiny, rice-grain-sized shells she gathered at Tule Lake.

One of her sons, by counting the number in a quarter-teaspoon and extrapolating from that, calculated the jar holds about 120,000 shells, roughly one for each man, woman and child at the camps.

Many took their stories to their graves, telling few people what they experienced.

For Gruenewald, who speaks to college classes, civic organizations and other groups, those memories are important to share, but always will be painful.

"It took a long time," she said, "to give myself permission to cry in public."

Copyright NewSage Press, 2006.