|

|

|

|

|

|

Young Reader's Edition |

|

ISBN 978-0-939165-58-2 |

Above, barnyard swallows dipped and soared through the gray, still sky, twittering sporadically. Turbulent thoughts and feelings swirled through my mind and heart. Why is this happening to us? What have we done to justify such a drastic order?

I turned to Mama-san and asked, “Why do we have to leave? Why are they making us go?”

Mama-san turned her sad eyes towards me and quietly said, “Japan has attacked Pearl Harbor. There is fear that she will attack the West Coast. It is best that we leave.”

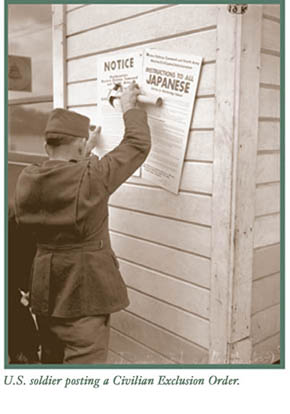

Somehow, her answer didn’t feel very satisfying. I had never been away from home, even to a friend’s house, for more than one night. Now I was leaving against my wishes, perhaps forever, and I didn’t even know where we were going. Having lived on a berry farm on an isolated island, I was totally unprepared for any disruption to my life, much less one as big as this. We were among 110,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans living in Western Washington, Oregon, and California ordered to leave our homes.

Somehow, her answer didn’t feel very satisfying. I had never been away from home, even to a friend’s house, for more than one night. Now I was leaving against my wishes, perhaps forever, and I didn’t even know where we were going. Having lived on a berry farm on an isolated island, I was totally unprepared for any disruption to my life, much less one as big as this. We were among 110,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans living in Western Washington, Oregon, and California ordered to leave our homes.

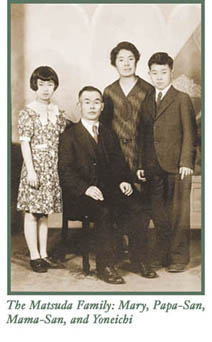

I looked at Papa-san, who moved steadily forward, his eyes staring straight ahead, shoulders squared, lips pressed tightly together. A resolute look on his face belied the realization that he could not protect his family from this looming threat. Yoneichi mirrored our father, moving ahead with firm steps, his face sober, his jaws set firmly together. Mama-san followed several paces behind, her sad eyes cast down. Dragging my feet I walked beside Mama-san, feeling empty and confused. I was old enough to know that something was dreadfully wrong, but still frightened, like a lost child. We said nothing. Much of our family communication was done silently through a glance or a body posture.

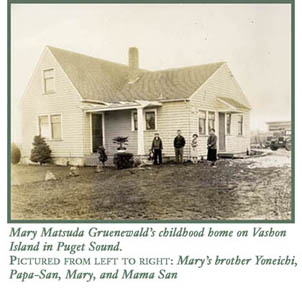

I looked south to our neighbor’s berry farm with its neat rows of currant bushes loaded with blossoms. I thought, It’s going to be a good crop this year for the McDonalds. That’s great because they’re good people. Eleven years earlier when we first moved into our new home the McDonalds were the first to greet us. That evening they gathered several neighboring families to surprise us with a shivaree. We didn’t know until then that the loud pounding of pots and pans and shouting was the typical way of welcoming newcomers in this rural community. We were overwhelmed by all of the good food and drink they brought us. This confirmed what my parents had told Yoneichi and me many times: “This is a wonderful country to live in.” Although my parents were from a different country, it didn’t matter to our Vashon neighbors. Their friendly welcome reinforced their assurances that tolerance and acceptance of people’s differences were real in this community. Every spring after that shivaree Mama-san took boxes of big, sweet, sun-ripened strawberries, the first and best of the season, over to the McDonalds and our other neighbors. That morning as we left our home I wondered wistfully, Will such a time come again?

As we passed by the Peterson’s home and their chicken ranch, I thought about how kind and understanding these neighbors had always been. Mr. Peterson was tall and lanky, but slightly stoop-shouldered from hunching over all the time tending to his chickens or their eggs. I used to buy eggs when our hens were not laying because his chickens’ eggs were always fresh and good. I often found Mr. Peterson in a special little room located in the midst of the chicken houses where he sized the eggs. I loved to watch him as he showed me how he sorted and cleaned the best ones for market. Mrs. Peterson would invite me in for a cookie and a glass of milk whenever she saw me come.

As we passed by the Peterson’s home and their chicken ranch, I thought about how kind and understanding these neighbors had always been. Mr. Peterson was tall and lanky, but slightly stoop-shouldered from hunching over all the time tending to his chickens or their eggs. I used to buy eggs when our hens were not laying because his chickens’ eggs were always fresh and good. I often found Mr. Peterson in a special little room located in the midst of the chicken houses where he sized the eggs. I loved to watch him as he showed me how he sorted and cleaned the best ones for market. Mrs. Peterson would invite me in for a cookie and a glass of milk whenever she saw me come.

One morning in the fifth grade I missed the school bus and was running down the highway as fast as I could. Before I got a quarter of the way to school, Mr. Peterson came along in his pickup truck and stopped. “Missed the bus, huh? Jump in.” Away we went, getting to school before the bus. These simple kindnesses loomed large as we walked away from our community, following government orders against our will.

When we were still about a quarter of a mile from the Morita’s, we were startled to see covered army trucks lined up along the street. Soldiers stood at attention with rifles and fixed bayonets. We all stopped. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Are we going to be treated as prisoners of war and executed?

Papa-san set his suitcases down without taking his eyes off the trucks. His eyes narrowed and his jaw tightened. “Army trucks.” His shoulders slumped. Under his breath I heard him whisper, “I wonder what this means.” This was the first time I ever saw my father broken. Seeing him defeated terrified me.

Papa-san set his suitcases down without taking his eyes off the trucks. His eyes narrowed and his jaw tightened. “Army trucks.” His shoulders slumped. Under his breath I heard him whisper, “I wonder what this means.” This was the first time I ever saw my father broken. Seeing him defeated terrified me.

Yoneichi’s body stiffened and his face turned ashen. He tightened his grip on his suitcases. He answered Papa-san in a clipped voice, “Yeah, looks bad.” He lowered his face, but his eyes remained fixed on the trucks, as if to ask, “Those guns, are they going to finish us off before we leave the island?”

Mama-san sucked in her breath and held it as all the color drained from her face. Slowly she exhaled as if she had only enough breath to say, “Kowai na—This is scary, isn’t it?” My throat tightened, my heart started pounding, and I broke out in a cold sweat. Seeing my family’s reaction terrified me. I had to force myself to resume walking, asking myself repeatedly, What have we done to deserve this?

As we neared the designated area, it looked as if the soldiers were ready for any disorder, any disturbance, any disruption, as if they thought some of us might resist or get out of hand. One soldier in particular watched my family. His piercing dark look searched our faces, evaluating the seriousness of the threat we posed. With his glare and his rough actions he communicated, “No bullshit from you Nips. I mean business!” Holding his weapon in his right hand, his finger on the trigger, he pointed with his left to the place to deposit our luggage. “Over there,” he shouted, his upper lip curled into a snarl. His words exploded contempt and scorn. I couldn’t let myself consider the possibility that he might take us away somewhere to shoot us. I wanted to cry but I didn’t dare. I had to force myself to follow instructions.

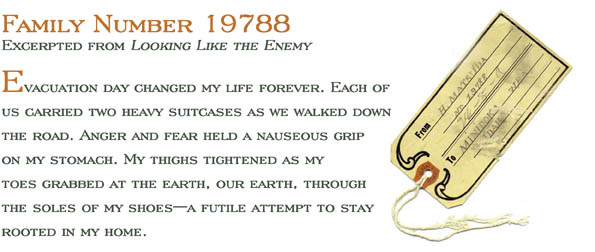

We put our luggage together on the ground behind the trucks as directed. Another soldier with a much softer tone of voice gave us tags and our family number, 19788. He looked at each of us and said, “Be sure to put that number on these tags and put them on each piece of luggage. You’ll be identified as members of the same family, so be sure to put it on your coat or sweater, too, where we can see it.” The tag was to dangle clearly in view wherever we were. Now I had become just a number, counted and labeled as the enemy.

We put our luggage together on the ground behind the trucks as directed. Another soldier with a much softer tone of voice gave us tags and our family number, 19788. He looked at each of us and said, “Be sure to put that number on these tags and put them on each piece of luggage. You’ll be identified as members of the same family, so be sure to put it on your coat or sweater, too, where we can see it.” The tag was to dangle clearly in view wherever we were. Now I had become just a number, counted and labeled as the enemy.

While we waited for the others, Mrs. Watanabe arrived. I groaned inwardly when I saw her. Whenever she came over to our place she always chattered endlessly about things that held no interest to me. Mama-san was always polite, but I knew Mrs. Watanabe was looking at me to evaluate my potential as a future good wife for some Japanese boy. I was annoyed with that. Incredibly, given the circumstances, Mrs. Watanabe was her usual inane self. She talked non-stop, this time complaining about the situation. I just wanted her to shut up. Mama-san acknowledged her with a slight bow and a faint smile, but her face remained impassive. This was no time for chatter about trivial things.

More families arrived. At the sight of the armed soldiers, they all looked frightened and whispered to each other. The children fell silent, huddling close to their parents. The adults were tight-lipped, their eyes darting from the soldiers to the guns to the line of army trucks nearby. I stood close to Mama-san and found comfort in our shared silence.

We had no idea where we were going that fateful day as we waited. I did not know what the bigger picture was, and I didn’t know if the government did either. All I knew was that all of us of Japanese descent would be affected.

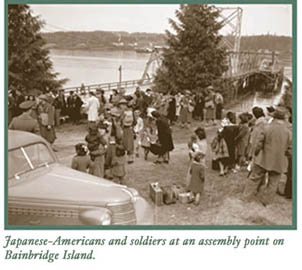

By 10:00 a.m. the Japanese families on Vashon Island—126 people in all—had gathered at specified assembly sites. The soldiers dispassionately directed us to climb aboard the trucks and insisted that we crowd close together. A sturdy box was in place for us to use as a step stool to climb aboard. Yoneichi helped the older women as they took the gigantic step into the truck. Most were dressed in their finest Sunday clothes with silk stockings and nice shoes. One by one we silently and grimly climbed aboard and sat along the sides of the truck and then on the benches placed along the middle. The soldiers piled our luggage around us before we started for the Vashon Heights dock. I took my place on the uncomfortable bench, avoiding eye contact with those across from me. I felt ashamed and dirty despite my tidy appearance. No one said a word, not even Mrs. Watanabe.

The caravan of trucks snaked through the small town, past the Methodist Church that had been such a part of Yoneichi’s and my life. Through tear-filled eyes I caught a glimpse of the newly painted theater, the post office with the American flag fluttering, the Alibi, a restaurant with its sign painted boldly above the doorway, the well-stocked hardware store and Tim Clark’s drugstore. I thought about the day in 1933 when there was a fire in downtown Vashon. They dismissed church service and Sunday school so the adults and older boys could help remove merchandise from the store. The owners of the drugstore gave away free ice cream cones to everyone because they knew it would melt without electricity. In my childish innocence, I felt lucky that day to get one.

We passed Vashon Grade School and the gymnasium where I played with my friends. From inside the dark, noisy truck that memory seemed a long time ago. Now we all rocked back and forth in unison as the truck lumbered along the bumpy road, twisting around tight turns in the final descent to the ferry terminal.

The ferry dock was familiar yet strange. Hundreds of people milled around with a sense of foreboding. I was stunned to see many of our non-Japanese neighbors and friends from church and school at the dock. They had gotten word of the evacuation and had come down that Saturday morning. As each of my classmates came up to me for final words, I found it hard to say anything.

Bob came up and said, “Mary, I don’t know what this is all about, but it all seems so unfair. I will really miss you. Do you know where you are going?”

“No, I have no idea.”

Even Shirley, one of the most popular girls in our class, approached me and said, “Boy, this is terrible. Will you write to us so we can stay in touch?”

“I promise to do that,” I responded, surprised that she would take the time to come to see me off. I didn’t know she cared that much.

One of my closest Sunday school friends, Angie, said, “Take good care of yourself and your folks. We’ll be praying for you.”

“Thanks, Angie. I’ll miss you.” What I wanted to say to Angie was, I’ll always remember that time you and your brother took me out on Puget Sound in your sailboat. It was so quiet and peaceful out there with the light warm breeze moving the boat gently through the smooth water. That was the only time I have ever been out on a sailboat and it was so much fun. But I couldn’t bring myself to say it out loud for fear that I would cry uncontrollably.

A ferry finally arrived, but this was not the usual ferry we sailed on all the time. It was smaller, old, and gray. Slowly it moved into place, then the workers tied it off and positioned a gangplank. I hugged my friends and said my tearful goodbyes. As I started down the gangplank, I had to blink several times to see where I was going. We descended into the unknown. It was now about 12:30 p.m.

The soldiers followed us aboard, then a worker raised the gangplank with a loud clang. As the ferry began to move out into the Sound, everyone on the dock began to wave. Angie had one arm around her dad’s waist as she waved her handkerchief with the other. She kept wiping her eyes with the handkerchief, calling out, “Goodbye, goodbye.” The words floated across the waves as the ferry moved farther away.

My legs felt heavy, glued to the deck. I thought my lungs would burst from holding back my sobs. The voices from the dock became fainter and fainter until I could no longer hear them. The dock and the people grew smaller, but I couldn’t stop looking until they disappeared.

The ferry made another stop to pick up more families on the west side of Puget Sound at Kingston. It was late afternoon before we arrived at Pier 52 in Seattle. By then I was exhausted from standing and staring for hours at the water.

Soldiers directed us toward a waiting train not far from the ferry landing. People gathered on the streets and the overpass nearby to watch us being escorted by armed soldiers. We had to walk past the silent glaring crowd. I noticed a long string of cars parked along both sides of the street where we had to walk. My stomach knotted up when I saw a group of restless, angry-looking men with dirty coveralls standing along the sidewalk, each nervously fingering a shotgun. One ruddy-faced, tall, heavyset man with deep vertical lines between his eyebrows acted like the leader. His steel gray eyes bulged as he lifted his gun with one hand and shook his clenched fist with the other. “Get outta here, you God damn Japs!” he shouted. “I oughta blast your heads off.”

Dropping my eyes and head, I walked quickly past him. The other men didn’t say anything, but they spat at us as we passed. Most of the crowd just stood and watched. Hurrying past, a thought crossed my mind. Maybe it’s a good thing we’re leaving. Maybe hysteria over the war news and the media frenzy could make it too dangerous for us to remain here. Maybe the government is trying to protect us. I was too frightened to make any sense out of it.

Silently we walked to the train about one hundred yards from the dock. We boarded and looked for a place where we could sit together. Making my way down the aisle, I realized immediately these cars had not been used in a long time. There was a strong musty, acrid smell and the seats and floors were dusty and dirty. All the windows were shut and smoked to block the view outside. There would be no way of knowing where we were going. A sense of isolation and impending doom rose.

Families tried to stay together and for the most part, this was possible. Eventually, everyone was aboard, including the soldiers. The train lurched forward into the night toward an unknown destination.

I had never ridden on a train before. Occasionally Papa-san and I took a streetcar to downtown Seattle to go to the optometrist. On those days, Papa-san and I would get all dressed up, catch the bus out on the highway, and ride to the ferry. After the twenty-minute crossing, we walked down the long dock to the streetcar station nearby and rode into Seattle. I enjoyed looking at all the houses built so close together with such small yards compared to ours in the country. As we approached downtown, Papa-san usually pointed to the one tall thin building and said, “See that building over there? That’s the Smith Tower, the tallest building west of the Mississippi River.” I was impressed.

After the doctor’s visit, Papa-san and I always went to Japantown to my favorite restaurant, Maneki’s, to have buta-dofu, pork and tofu with rice and miso soup. The waitresses always recognized us and welcomed us for lunch. Having to change my glasses almost annually was a nuisance, but those trips to Seattle with Papa-san were such a treat. I always felt special being with him. I also saw how Papa-san moved easily among business people, both white and Japanese, and noticed how comfortably he could engage in conversation with friends and strangers alike. I was proud of my Papa-san.

This train ride was nothing like those trips. Looking around at everyone’s grim and stoic faces, I felt afraid and frustrated that no one could say where we were going or why. People spoke only in brief and hushed tones to one another. Even the children were subdued. There were so many people in our car, some standing in the aisles, we had to squeeze by one another to get to the restroom. Once when I tried to get back to my seat, I found that someone else had taken it. When I went looking for another place to sit, I found one on the top bunk of a sleeper car. There were many girls sprawled up there, none of whom I knew.

One of the tall, good looking soldiers laughingly said to us as he walked down the aisle, “Hey, why don’t some of you beautiful girls come three cars back to our car. There’s plenty of room, and we’ve got some great grub, booze, and music. It’d be a heck of a lot more fun than being cramped up there.”

One of the girls giggled and said, “Hmm, I wonder what that would be like.”

Another answered, “Do you think we should go or not?”

“It sounds like it could be fun,” the first girl replied. “It’d sure beat what we got here.”

“Do you want to go for a little while, just to see what’s back there?” Something inside of me said, No, that’s not a good idea. I may be seventeen years old but I’m not ready for doing that sort of thing yet. Finally two of the girls did get down and the last I saw of them they were worming their way toward the back. I have no idea what happened to them.

The girls on the bunk talked about how hot and stuffy the air was becoming. I dozed off and on. I did not like being crowded together with so many strangers, even if they were Japanese. The one comfort I had was that our little family, Papa-san, Mama-san, Yoneichi and I were all on the same train. We were all going to the same place—or were we? Then I began to worry. I got down from the bunk and when I found my parents, I asked Papa-san, “Do you think we are all going to the same place?”

He dropped his eyes, thought a minute before he looked at me and replied, “I don’t know, Mary-san. We’ll do everything we can to stay together.”

Fear gripped my heart. What would I do if we were separated from each other? What would become of my parents and what would become of me? I wanted to grab his hands and never let go. I broke out in a cold sweat. I couldn’t shake this foreboding thought. I stood in the aisle beside his seat for a long while before I found a place to sit down.

We rode on the train for about three days, punctuated by occasional unexplained stops of various lengths. At regular intervals, soldiers distributed bagged meals, consisting of tasteless sandwiches, apples, and water. Some of us thought we must have been going south because it kept getting hotter. At one point I felt hot and cold simultaneously and slightly nauseated, then I only saw blackness. A short time later I awakened to see Mama-san and other people scurrying around me, wiping my face with a cool, damp cloth. Someone even got a window cracked open and we finally had some air circulating through the car. That was the only time in my life I ever fainted.

We could not have known at that time that some families initially would be housed in hastily modified “assembly centers,” including livestock stalls and stables. Evacuation centers would include fairgrounds in Portland, Oregon, and Puyallup, Washington and the Santa Anita Race Track and the Tanforan Race Track in California. Years later we would learn through word of mouth that some of the people who were sent to these foul places became very ill, with vomiting and diarrhea caused by the urine and feces-saturated environment of the livestock stalls in which they had to live. Our train rumbled towards an unknown destination, carrying us to some place, somewhere, for some unknown length of time, and possibly to our death. Uncertainty was all we knew.

Copyright Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, 2006.