|

|

|

|

|

|

Young Reader's Edition |

|

ISBN 978-0-939165-58-2 |

![]()

Originally published 18 February 2012 at 03:11 ET

Pain and redemption of WWII interned Japanese-Americans

By Cordelia Hebblethwaite

BBC World Service

Seventy years ago, in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attacks, the US West Coast was cleared of Japanese-Americans. More than 110,000 people were put into internment camps, in what was the largest official forced relocation in US history. For many who lived through it, the story remains a painful one.

Now aged 87, Mary Matsuda Gruenewald cuts an elegant and strong figure. She speaks vividly and with almost photographic detail as she recalls the time she and her family spent in internment camps during World War II.

But it wasn't always so - it was only many years after she left the camp that she felt able to tell the story, even to her own children.

"I was afraid that if I started talking about it, I would cry.

"And I didn't want to cry in front of my children, so I kept it all in."

Mary was 16 years old at the time of the Pearl Harbor attacks, and had been living an idyllic life on Vashon, a small rural island just off the coast of Seattle.

Her parents ran a strawberry farm, and were regarded as upstanding members of the community - good, hard-working and church-going.

Mary and her brother Yoneichi were born in the US, and considered themselves both American and Japanese. So they were just as shocked as the rest of the nation when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, killing more than 2,400 Americans.

The nation was now at war and, because of their Japanese connections, they overnight came to be seen as the enemy.

"We were not white and so we stood out - there was no way for us to hide."

"The propaganda in the newspapers, on the radio, in the magazines, the caricatures - all this was overwhelming, and it just kept coming and coming," she recalls.

"We knew that something really bad would happen to us - we just weren't sure what it would be."

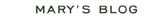

Leaving homeOn 19 February 1942 - just over two months after Pearl Harbor - President Franklin D Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It allowed the military to designate "exclusion zones" and cleared the way for the removal into internment camps of more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans.

The government feared Japan's next move might be an attack on the US West Coast, and that the large community of Japanese-Americans living there might act as spies or collaborators.

The public was right behind the measures.

"There was very little dissent at the time," says Prof Greg Robinson, a historian at the University of Quebec at Montreal, and author of A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America, and By Order of the President.

"On the West Coast the political class was for it. In the rest of the country, people really didn't know or care - they just thought if the government was moving people, they knew what they were doing."

In May 1942 that order became a reality for Mary. Her family were given eight days to leave their homes.

"We didn't know how long we would be going for, or where we would be going," remembers Mary.

She packed enough socks and underwear for one week, together with one coat and one pair of shoes.

Each family had a number assigned to them and were given tags to wear.

After arrival in Seattle, Mary and her family were walked past a large crowd of the city's residents.

"A few men swore at us, and shook their fists, and some spat on us.

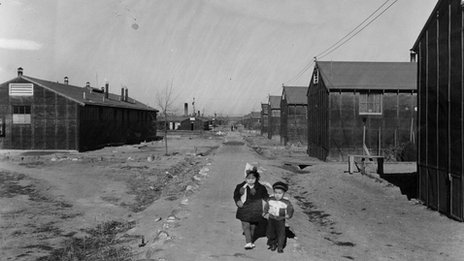

The Minidoka Internment Camp in Idaho, one of the camps that housed Mary

The Minidoka Internment Camp in Idaho, one of the camps that housed Mary

"But the majority were silent as they watched us walk from the ferry dock to the waiting train."

The windows on the train were obscured and no-one knew where they were headed.

After three days, the train stopped at Pinedale, near Fresno in California, and an Assembly Centre where Mary and her family spent the first two months before being moved to the Lake Tule camp, and then a further two camps over the years.

Life insideThe accommodation in the internment camps was basic - army barracks divided into a number of compartments.

Mary's family stayed in a bare room approximately 20ft x 24ft (6m x 7m) with one small window and a bare light-bulb. They were each given a woollen blanket and an army cot for a bed.

Like many of those who were interned, her family referred to their accommodation as their "apartment". It was however, she says, a euphemism.

"It was a prison indeed… There was barbed wire along the top [of the fence] and because the solders in the guard towers had machine guns, one would be foolish to try to escape.

"There were these big searchlights that rotated all night long and they would flash through our window."

There were schools in the camps, but - as with the living quarters - the facilities were basic.

Mary recalls how - in the absence of typewriters - typing classes involved tapping their fingers on an imaginary keyboard.

Many of the teachers were from inside the camps, but some came from the outside.

There were schools in the camps, but the facilities were basic

There were schools in the camps, but the facilities were basic

To the young students - confined, rejected and cut off from the wider world - they were a source of both curiosity and of comfort.

"We saw these teachers and we thought, 'Oh my goodness, this is a white person, in here, to teach us, why are they here?

"They were trying to act as a counterbalance to what the rest of the nation was doing, and we truly appreciated it," says Mary.

FreedomOne day they were given a questionnaire to fill in, asking whether they would be willing to serve in the US Army, and if they would pledge allegiance to the US and renounce loyalty to the Emperor of Japan.

Though they did not know it at the time, those who answered yes to both questions - as Mary's family did - would be classified as "loyals" and would be allowed to leave.

The young men, such as Mary's brother, were drafted into the US Army.

"As my brother got on the bus, drove through the gate and left, my mother and I wept, and wondered when it would be our turn to leave."

Her turn came soon afterwards, in August 1944, when she was sent to Chicago as part of the US Cadet Nurse Corps. She relished her new-found freedom and embraced it wholeheartedly.

"It was incredible - the sense that I could walk anywhere I wanted to, and enjoy the flowers, the grass, the trees and hear the birds - it was like being in heaven."

Two older nurses took her under their wing, treated her as an equal.

"I learnt a lot about what it means to feel despised, to be hated, to feel ashamed of who I was [during the internment].

Mary and brother Yoneichi returned in army uniforms to visit their parents in their Idaho camp

Mary and brother Yoneichi returned in army uniforms to visit their parents in their Idaho camp

"So to be treated as a responsible, respectful person, I can't tell you the relief and the awe that I felt."

Just over a year later, in September 1945, her parents left the internment camp too.

But, for many, the life they returned to was very different to the one they left behind.

"The best estimate that I have heard is that 75% of people [who] moved, ended up losing their land," says Prof Robinson.

"Everybody lost something and many people lost everything."

For years, many Japanese-Americans stayed silent about what had happened.

"The shame that came from this whole period permeated our people, and nobody talked about it," says Mary.

In the 1980s, the US government issued a report stating that the internment had been "unjust and motivated by racism rather than real military necessity".

President Ronald Reagan took steps to try to redress what had happened, which culminated in 1992 with an apology from President George HW Bush and $20,000 (£12,600) paid out to each surviving member of the camps.

Mary treasures the letter of apology she received from President Bush and only regrets that her parents and her brother died before it came.

"I took that as evidence that - in spite of the things the government did - this is a country that was big enough to say, 'We were wrong, we're sorry.'"

Copyright NewSage Press, 2006.